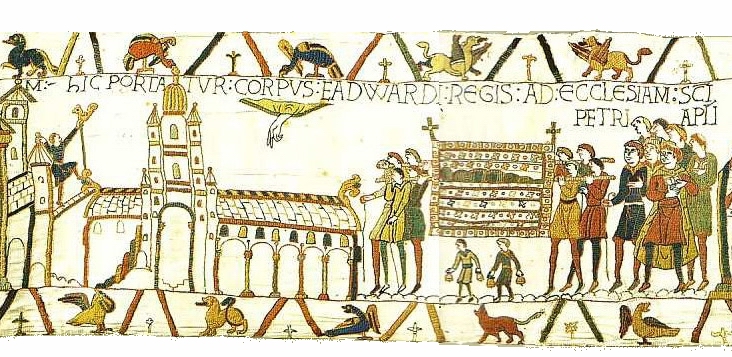

Nearly a thousand years ago,

in the 1070s, a 70’ long piece of embroidered cloth we now call the Bayeux

Tapestry was commissioned by William the Conqueror’s half-brother to depict the events leading

up to the Norman Conquest. One section shows the funeral of Edward the

Confessor, who died some months before the Battle of Hastings in 1066 (And All That).

If you look carefully at that scene, you’ll find - down at the bottom - two people carrying bells in each of their

hands.

The use of bells in religious ceremonies goes back a long way, in the West

at least to ancient Rome. And not just religious ceremonies. For many cultures around

the world from time immemorial have used bells to ward off evil spirits: in

India and China and Japan they used them alongside wind chimes. And the scene in the Bayeux Tapestry might

well be part of that tradition, the folk belief that evil could be averted by

frightening it off, so to speak, with bells. Wedding bells too, in

Christianity, belong in this tradition: they announce, and celebrate, the

couple – but they also ward off the evil that was felt to lurk whenever joy is

present.

These thoughts are prompted by a curious detail in this week’s Torah text. The robe of the High Priest, worn when he was performing his cultic duties, is described in elaborate detail in Exodus 28. It includes the instruction that his robe was to be adorned with bells on its hem (verse 35) – “and the sound shall be heard when he goes in to the holy space, before the Eternal One, and when he comes out, v’lo yamut”, (literally, ‘so that he does not die’). Archeologists in Jeruslaem have recently discovered such a bell near the Temple Mount.

As so often in the Torah, there’s no explanation given for these mysterious

bells. They can hardly be there out of a worry that the High Priest would get

lost – it’s not the sort of bells we put round

a domestic cat, or the Alpine bells round the necks of cattle or sheep

or goats. A traditional explanation

suggests that it could have been an announcing bell so that people would know

when the High Priest was entering the Holy of Holies for the sacred business of

communing with the Divine – a bit like the one that begins and ends that other

sacred activity, the opening and closing of the New York Stock Exchange. Or perhaps, like the pomegranates that also

adorned the hem of his robe, a symbol of the fruitfulness of religious life, the

bells were symbolic – representing connectedness with the divine, a connectedness

that goes beyond words.

Or perhaps it is evidence - to go back to the Bayeux Tapestry - of that

ancient belief that ringing bells can ward off evil? Don’t we all wish, profoundly wish, that we

could keep ‘evil’ away - stop bad things from happening - just by ringing a

bell? Whether it is ringing a bell, or spitting three times (p,p,p), or stroking

a rabbit’s foot, or not walking under ladders, or wearing an amulet blessed by

a wonder rabbi (or by the Kabbalah Centre), or any one of a hundred thousand folk

customs that have arisen in all ages and all places on the planet – how amazing

life would be if there could be a straightforward link between an action we

take (something we do, or say, or wear, or pray) and the warding off of

unpleasant, unhappy, upsetting, disturbing events, things that are part of the weave of life but cause us misery, pain, distress.

Beneath our rational selves, and our conscious, modern minds that might

describe all of these things as superstitions, as attempts to control life in

all its uncontrollable randomness, deep in us we can probably locate a

primitive emotional need to believe that we might have some way of controlling

our fate, of doing something that might prevent a disaster, or an accident -

for ourselves, or those we love. Harm can be avoided, we believe (we desperately

want to believe), if only I’m good enough, or pious enough, or superstitious

enough, or careful enough.

What we humans can’t bear, don’t seem to be able to bear - and our culture

colludes in this in all sorts of ways - is the sheer contingency of life, its

messiness, its unpredictability, its randomness, its haphazardness. You can get

into your car and if you are in the wrong place at the wrong time, you know

that, through no fault of your own, that you can be in an accident. It can

shake you up, it may even kill you – heaven forbid. And we say ‘heaven forbid’ –

or p,p,p as my grandmother would do - as a prophylactic: as if just by saying

those two words it could stop it happening. Or the parallel belief that if we don’t say it, it might happen: because now we have thought it, it just could

happen and we’d have brought it into being just by thinking it. We tie

ourselves in knots because if, in the end, what happens to us is out of our

control – that knowledge is unbearable, the feelings of helplessness are

unbearable.

We would all do anything to avoid these kinds of random events happening. We

would love to know how we can avoid distress and pain - but we can’t, and some part of us knows we can’t, knows

that life is not organized like that: even our bodies themselves are part of

that contingency sown into the fabric of life. We know our bodies are fragile, vulnerable, and we can look after

them as much as we can, eat the right things, exercise them, take care of them

- but they still let us down in unpredictable and uncontrollable ways.

Being an embodied human being is a daily lesson in the essential fragility

of our humanness – and our mental states

too are equally as vulnerable, however much we might meditate, or medicate, or

practice mindfulness, or however many years of therapy we might have had.

Bad stuff happens. And no bell ringing will make a difference. We are not

that omnipotent – even though lodged in us is an irrational belief that we are:

that we can manage our fate by just taking the right precautions; or having the

right security systems in place, in our homes, or synagogues, or computers; or

just following the right Health and Safety guidelines, or having the right

child protection schemes in place. One very modern illusion – a deeply needed

belief, but an illusion – is that we can legislate our way to happiness by

removing distress, or just alleviating the possibility of distress; that we can

have systems and laws to stop bad things happening to us, or to our children, or

to ‘the vulnerable’ – although we are all vulnerable. That is of the essence of

our humanity: our vulnerability, our mortality, – “never send to know for whom

the bell tolls; it tolls for thee” (John Donne, ‘Devotions Upon Emergent

Occasions’, 1624).

So although we don’t know – can’t know – the purpose of the bells on the

High Priest’s robe (the Talmud discusses whether there were 36 or 72 of them),

what we read is that these bells, on this garment, were a matter of ultimate

concern in the scheme of things. The Hebrew text intuits that what was going on

in these arcane rituals was a matter of

life and death. He was to wear these bells v’lo yamut, (‘so that he does not die’).

But maybe we can understand this phrase figuratively, and existentially. I prefer

to think that the wearing of these bells was v’lo yamut - ‘lest he stops

living in the moment’. By which I mean that these bells kept him alert, kept

him awake, moment by moment, every step of the way, every movement of his body,

even as he breathed in and out, as we all breathe in and out, the bells kept

him alive to the mystery, the awesome nature of being alive now, as we are

alive now – though we have no bells to remind us that this is a thing of awe:

human life, in all its fragility and vulnerability, all those cells, all that

DNA, all that drama of heart and lungs, liver and kidneys and bones and brain,

all that ‘three pounds of jelly’ (as Oliver Sacks, with well-tempered irony,

describes the brain ) through which everything flows and filters...what are we

to make of it all, this body of ours, this mind of ours, with its memories, its

feelings, its knowledge, alongside its limitations, its failures, its fading

powers? We have nothing as simple as a bell to remind us of the awesome nature

of life, daily life, our life, our being here now.

The bells kept the High Priest attentive to the mystery of being, at every

moment. Now and now and now. And this, I would suggest, is the holy space he entered – this awareness

of the present moment in all its kedushah,

its unfolding holiness of being . The Torah text gives us a picture not just of

an archaic ritual that has disappeared into the mythic past – but a picture of our

inheritance, we ‘kingdom of priests’ (Exodus 19:6). When we read of these bells

we turn our inner ears to the music of

the present moment - we are the priests whose task it is to enter into the presence

of the sacred: this music of the sacred, in each moment, is sometimes so soft

we can hardly hear it, it’s sometimes so quiet we forget to hear it, it’s

sometimes so faint we think there is nothing there.

We need to be reminded, every day, twice every day – Shema Yisrael, ‘Hear O Israel, Listen out Yisrael’, when we go out

and when we come in, the bells of the High Priest are still to be heard, each

moment, reminding us of the holiness of life itself. And if we don’t attune

ourselves to listening in – it is as good as being dead. This is the sacred

drama of a kingdom of priests, our daily drama, life-giving, life-preserving: it

is within the randomness of life, that

holiness is to be found.

The more time we spend trying to control life to avoid bad things

happening, the further we get from contentment. We can drive ourselves, and

others, mad If we cannot embrace life as – in the final analysis –

uncontrollable, as uncontrollable as those bells on the hem of the High Priest.

Every moment he moved, they sounded. Every moment he moved they reminded him:

you are alive now, and this is sacred. However still you are, you will hear the

bells, faintly, the background to life. It’s when you stop hearing the bells,

when the bells stop – that’s it, that’s the end of your life. The dead don’t

hear the bells. They are for the living, and for life. Shema

Yisrael.

[based on a sermon given at Finchley Reform Synagogue, February 8th,

2014]

Being an embodied human being is a daily lesson in the essential fragility of our humanness

ReplyDeleteThank you Howard. I love this. Deborah

Charm pendants are supposed to keep evil spirits at a distance and protects the wearer from the negative vibrations. These charm pendants are found at Online Fashion Jewelry Shopping stores.

ReplyDelete